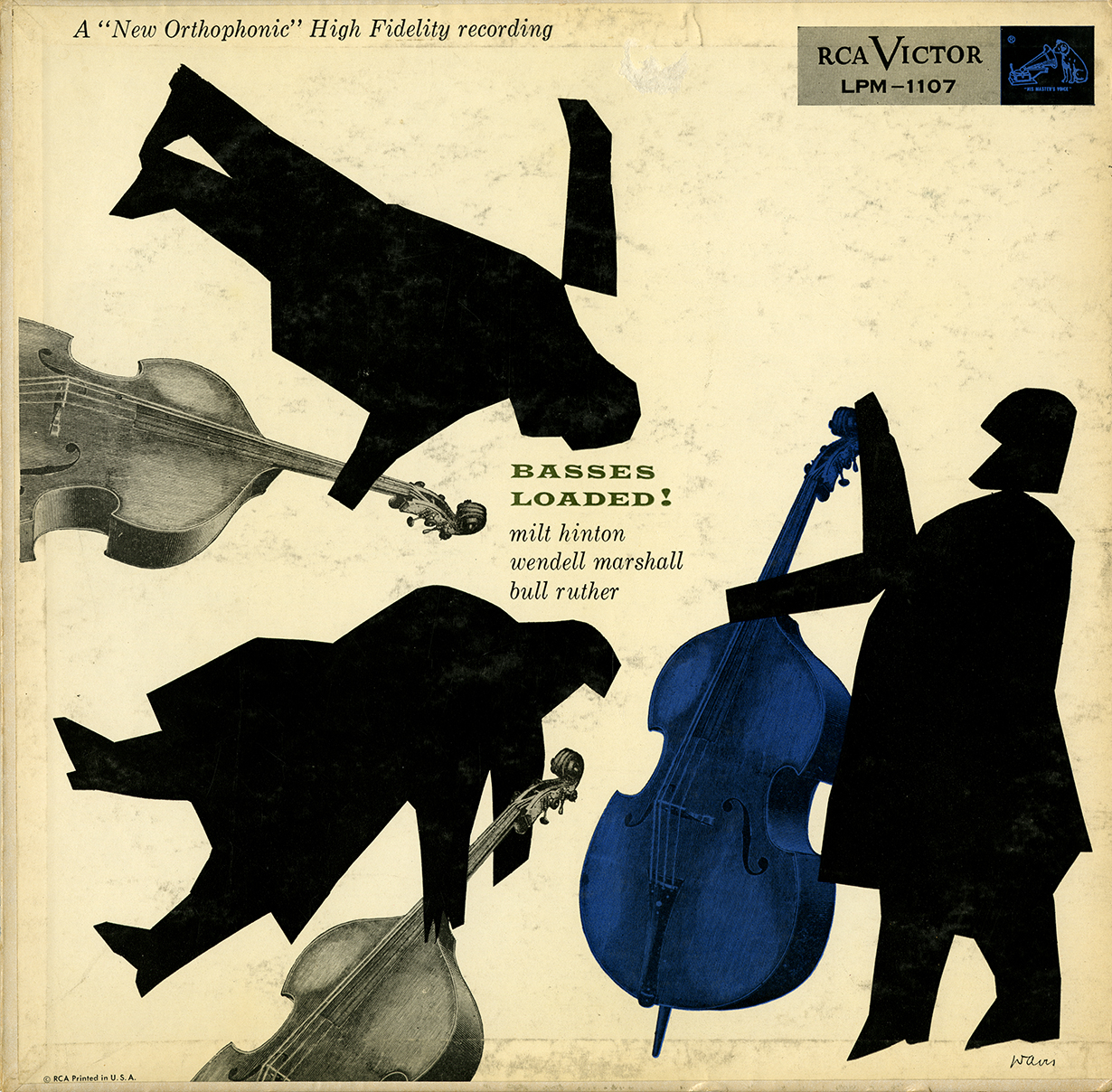

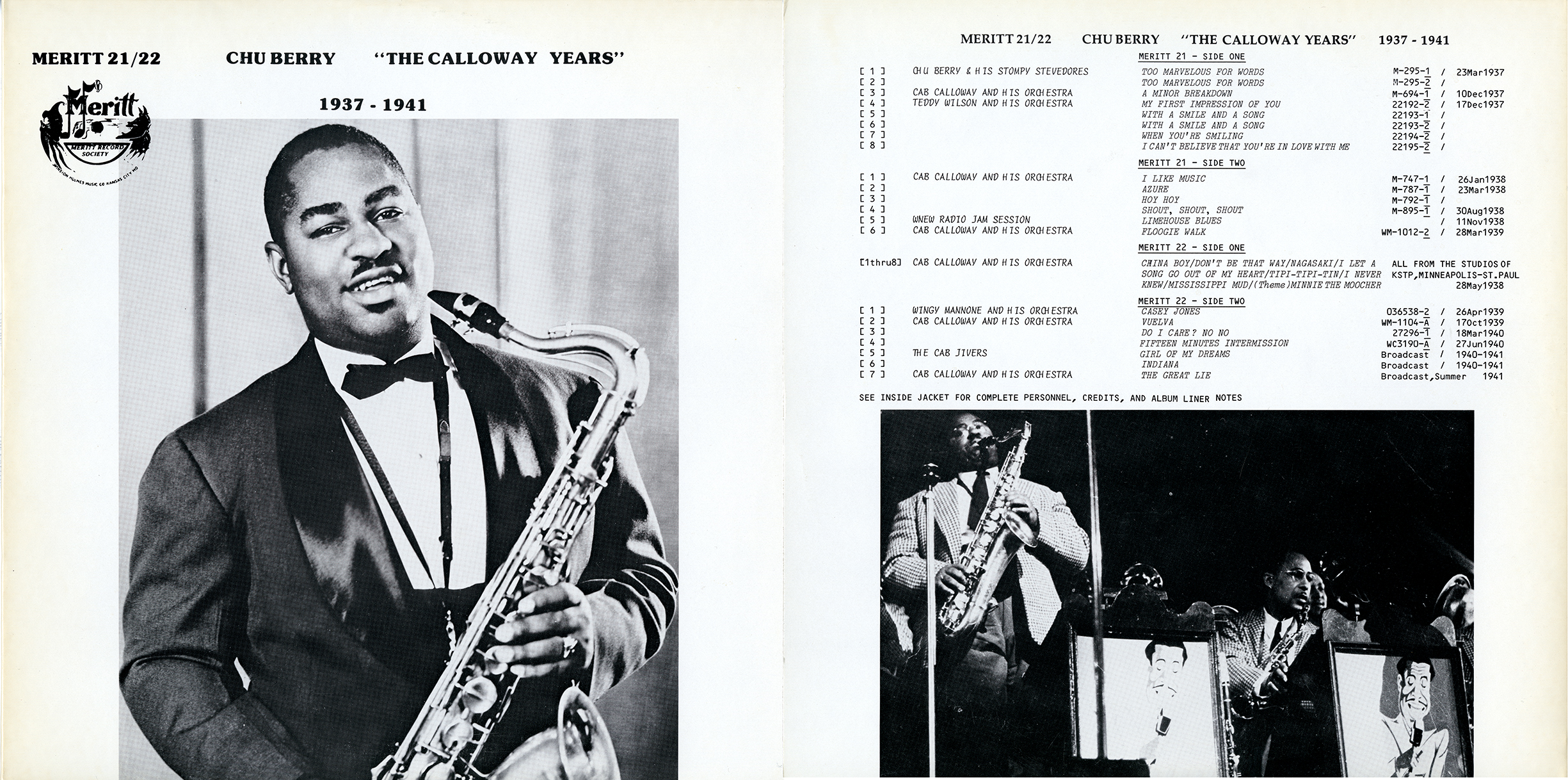

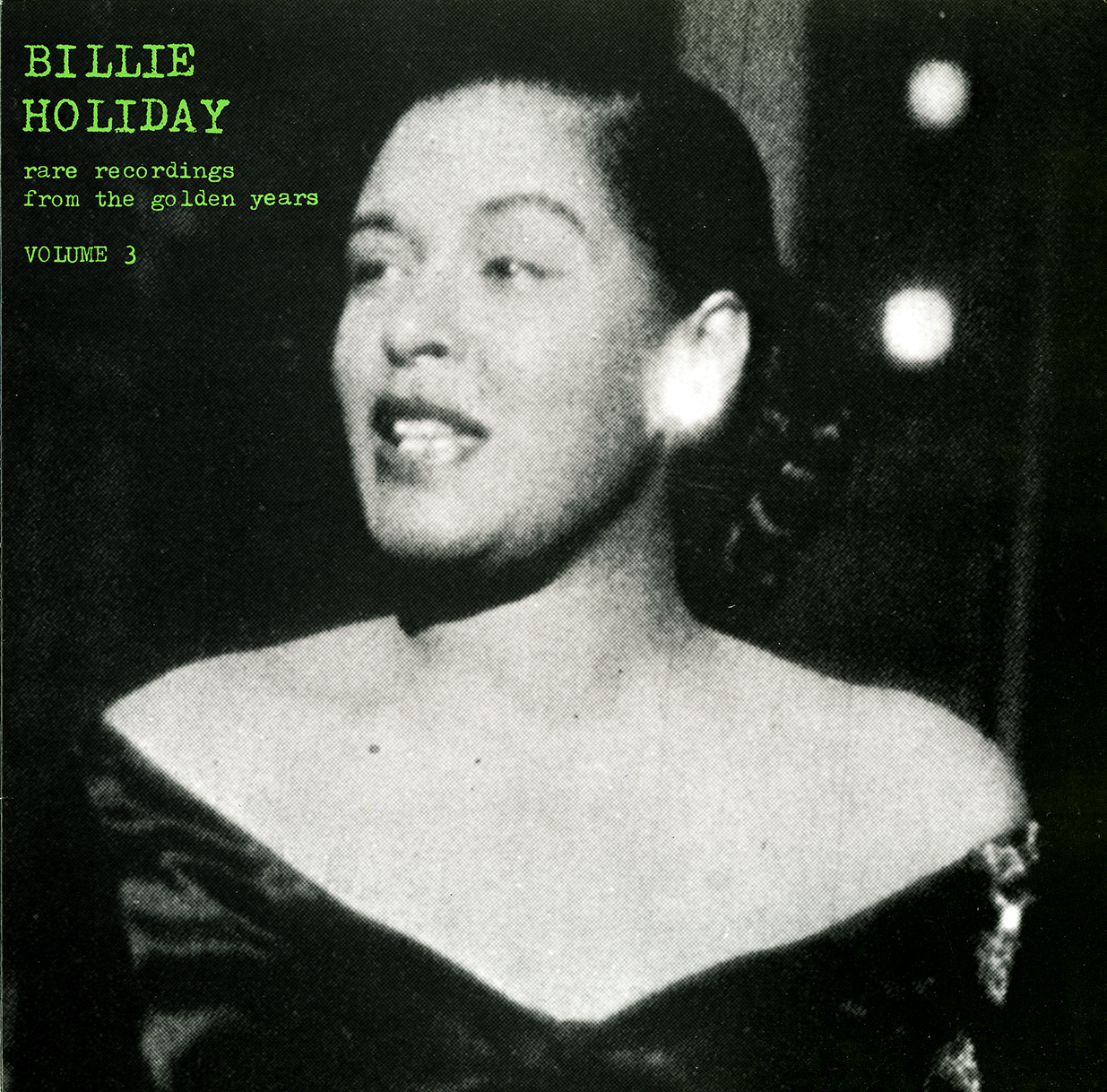

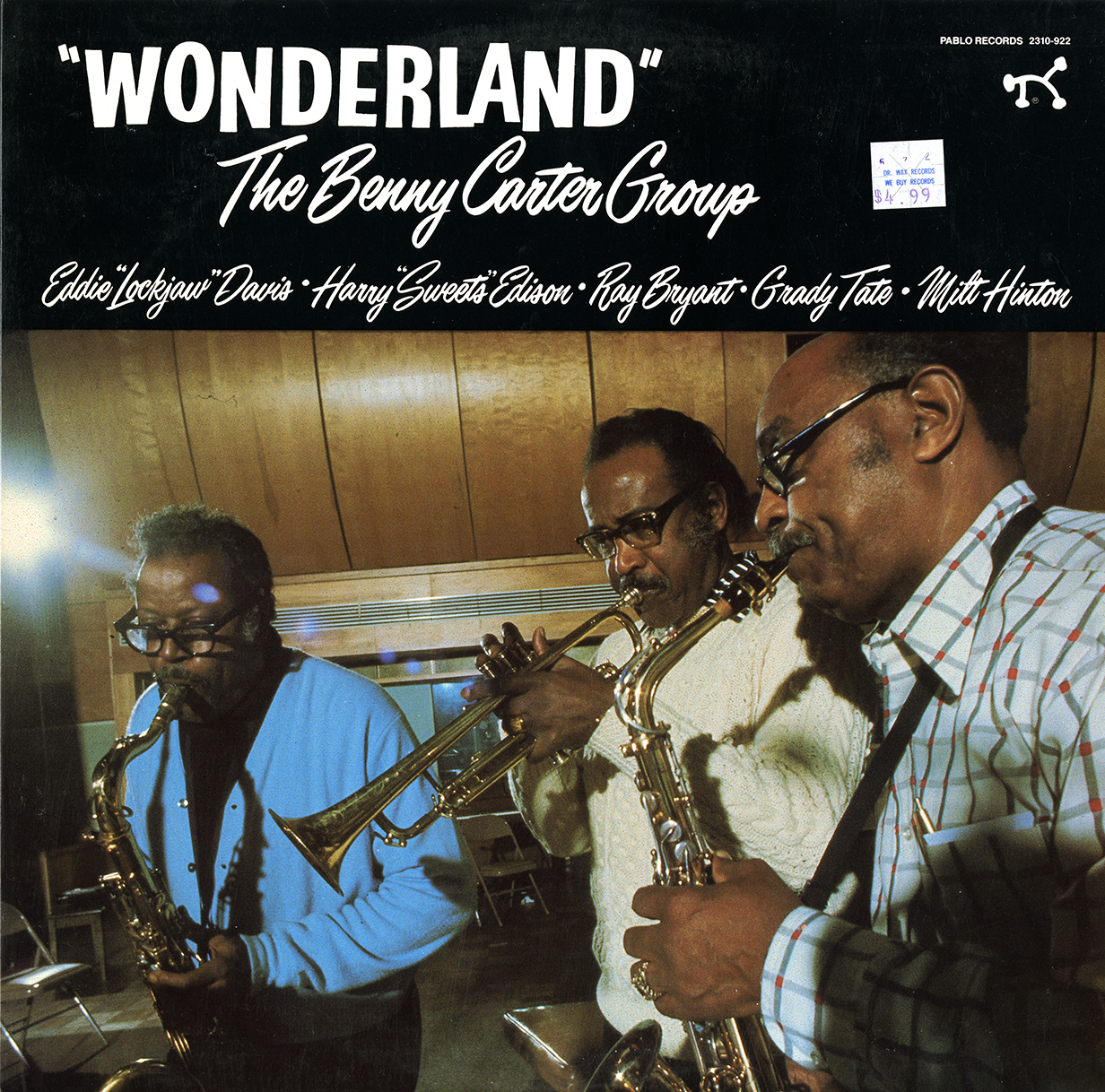

Discography

Milton John “Milt” Hinton (1910–2000)

Known as “The Dean of Jazz Bass Players,” Milt Hinton was an American double bassist and photographer. His nicknames included “Sporty” in Chicago, “Fump” on the road with Cab Calloway, and “The Judge” from the 1950s onward.

Early life in Mississippi (1910–1919)

Milt Hinton was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi, the only child of Hilda Gertrude Robinson, whom he referred to as “Titter,” and Milton Dixon Hinton. His father left the family when Milt was around three months old, so Milt grew up in a home with his mother, his maternal grandmother to whom he referred as “Mama,” and two of his mother’s sisters.

Hinton’s childhood in Vicksburg was characterized by extreme poverty and racial violence. The experience of unwittingly encountering a lynching formed “one of the clearest memories of my childhood.”

Growing up in Chicago (1919–1935)

Hinton moved with his extended family to Chicago, Illinois in the fall of 1919, which opened up a new horizon of opportunity for him. Chicago was where Hinton first encountered economic diversity among African-Americans, about which he later noted, “That’s when I realized that being black didn’t always mean you had to be poor.”

In Chicago, Milt experienced an abundance of music, either in person or through live performances broadcast on the radio. During this time he first heard concerts featuring Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, Earl Hines, Eddie South, and many others. Music was also a fixture at home, where Milt’s mother and other relatives regularly played on an upright piano. Milt received his first instrument—a violin—in 1923 for his thirteenth birthday.

While attending Wendell Phillips High School, he played violin in the school orchestra and learned peck horn in order to play in the school’s ROTC marching band that was directed by Major N. Clark Smith. He soon transitioned from peck horn to bass saxophone and then to tuba, while also being accepted into the city-wide brass band sponsored by the Chicago Defender, where he played alongside Lionel Hampton.

Milt Hinton depicted in his high school yearbook (1930), The Milton J. and Mona C. Hinton Collection, Special Collections, Oberlin Conservatory Library.

After graduating from high school, Hinton attended Crane Junior College for two years, during which time he began receiving regular work as a freelance musician around Chicago. He performed with such respected musicians as Freddie Keppard, Zutty Singleton, Jabbo Smith, Erskine Tate, and Art Tatum. His first steady job began in the spring of 1930, playing tuba (and later double bass) in the band of pianist Tiny Parham. Milt’s recording debut on November 4, 1930 occurred on tuba in the context of Parham’s band on a tune titled “Squeeze Me.” After graduating from Crane Junior College in 1932, Milt enrolled in Northwestern University for one semester, after which he chose to drop out of college in order to pursue music full-time. He received steady work from 1932 through 1935 in a quartet with violinist Eddie South, including extended residencies in California, Chicago, and Detroit. It was with this group that Milt first recorded on double bass in the spring of 1933.

The Cab Calloway era (1936–1950)

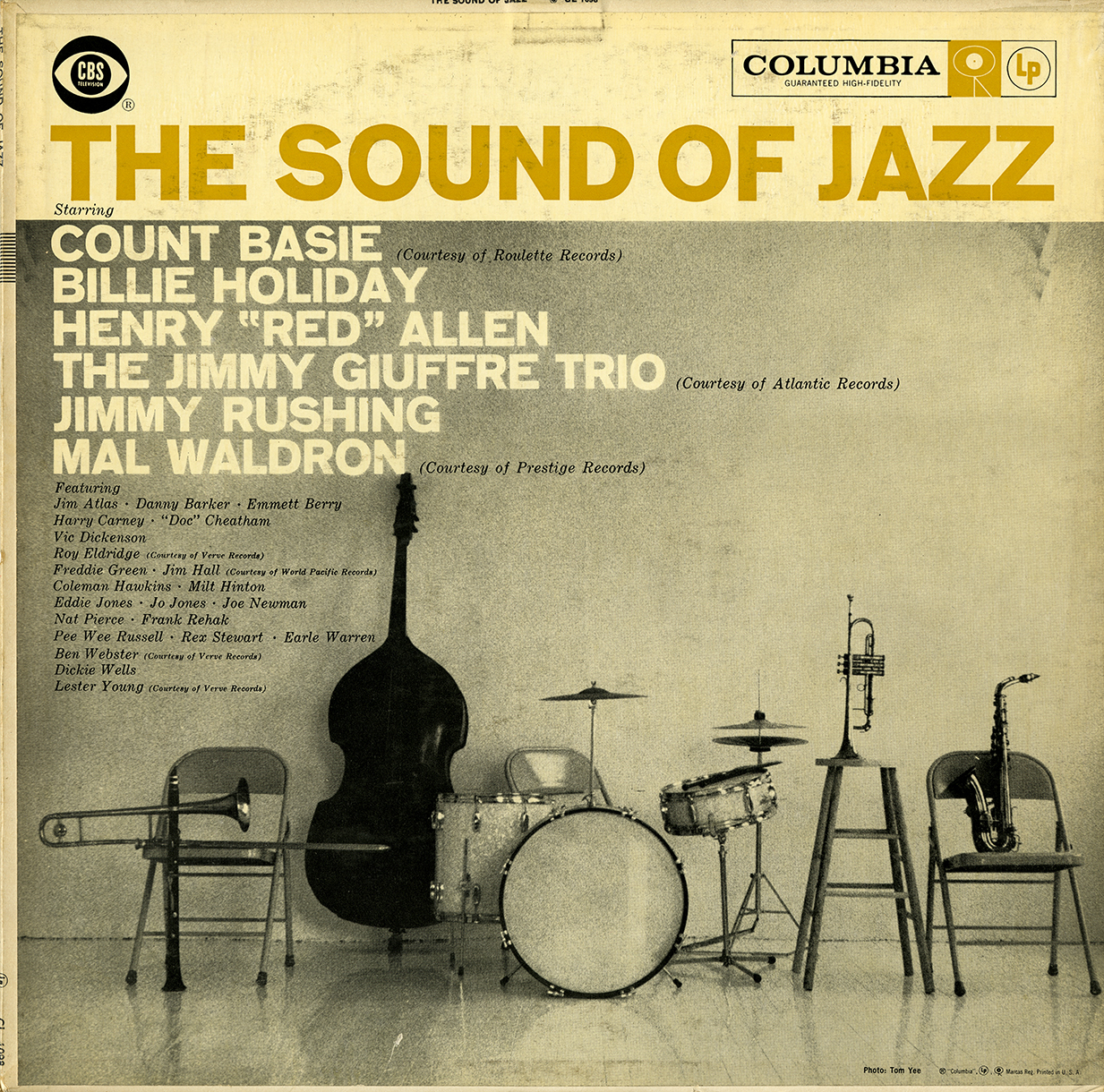

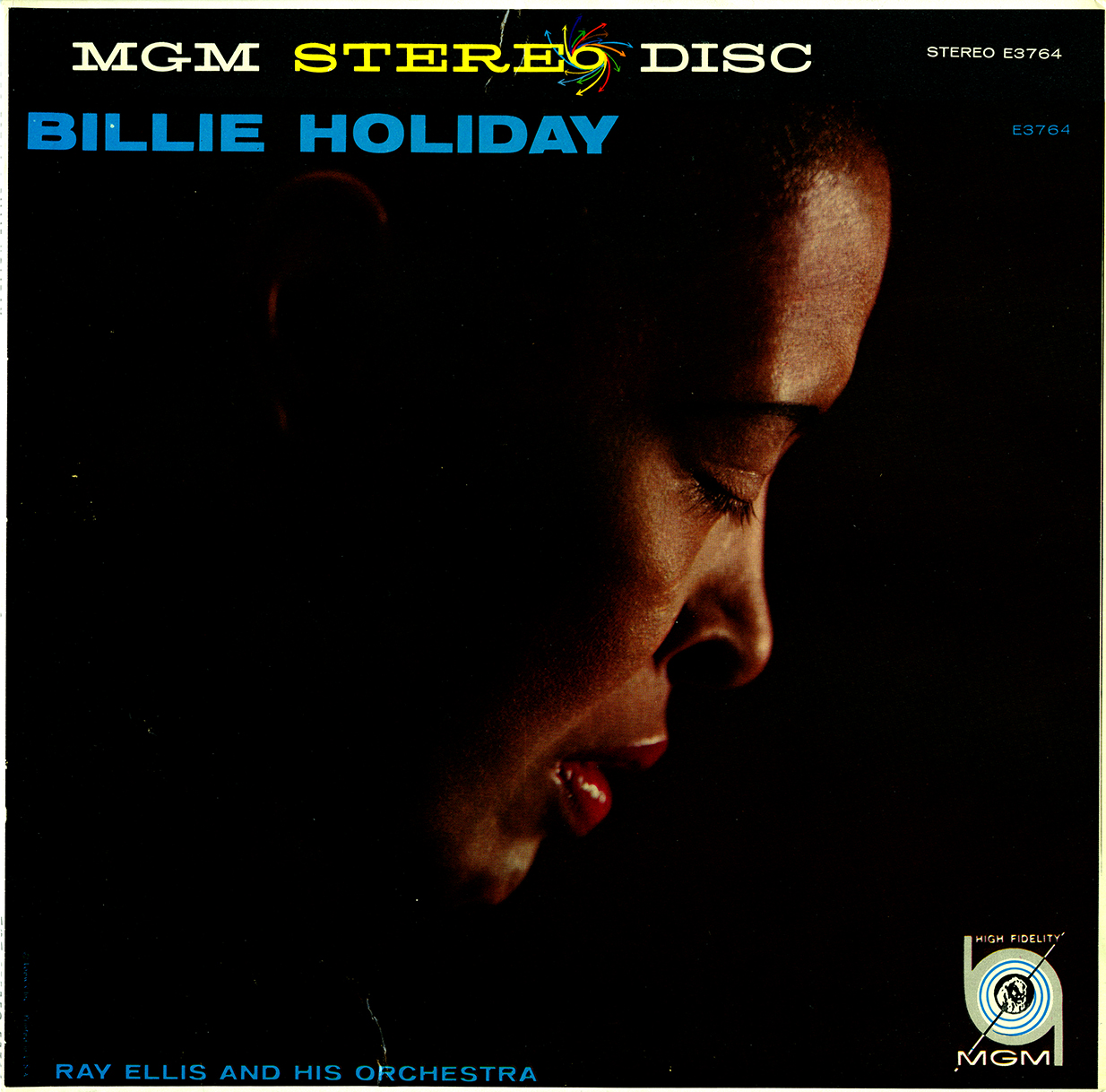

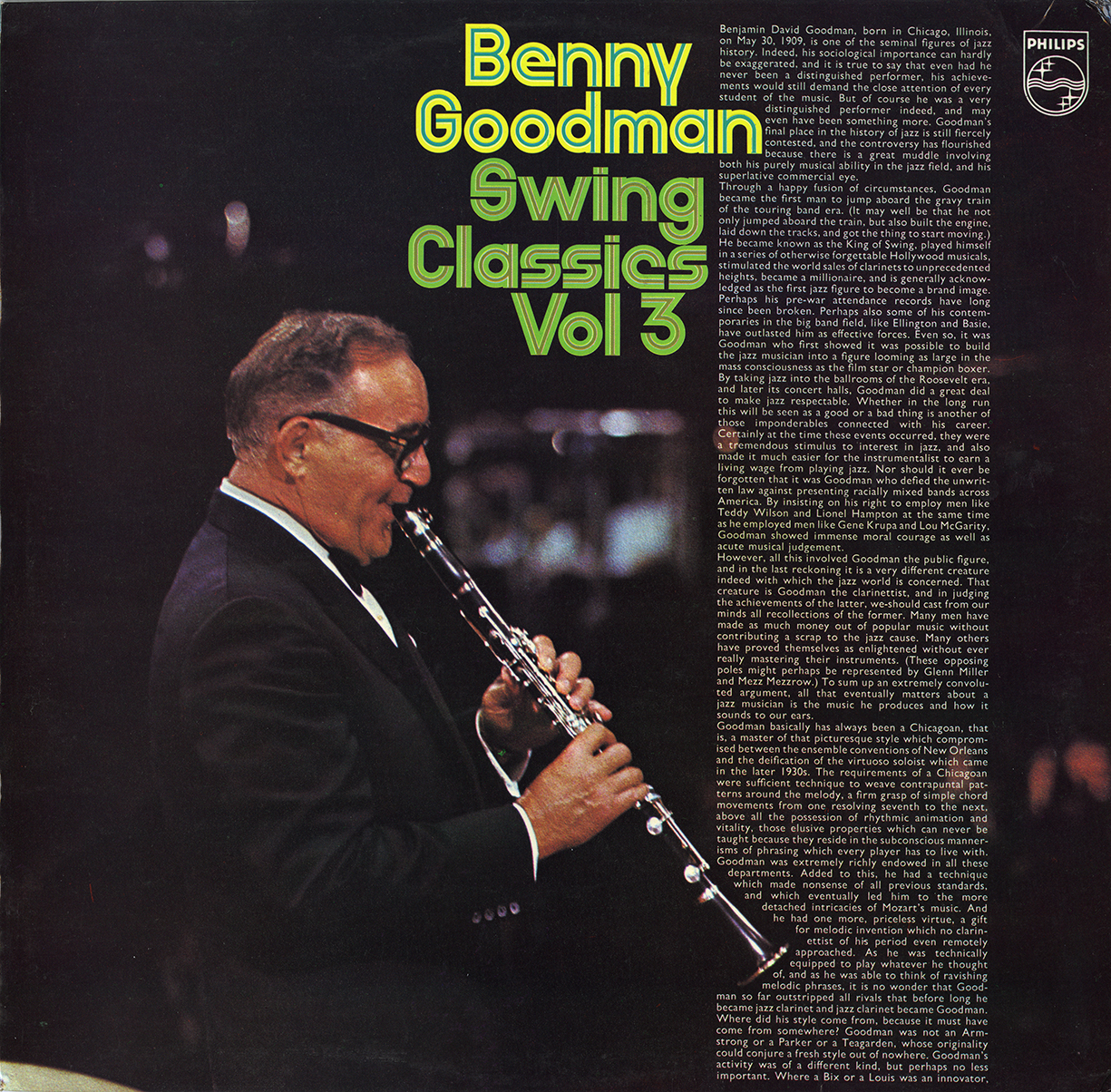

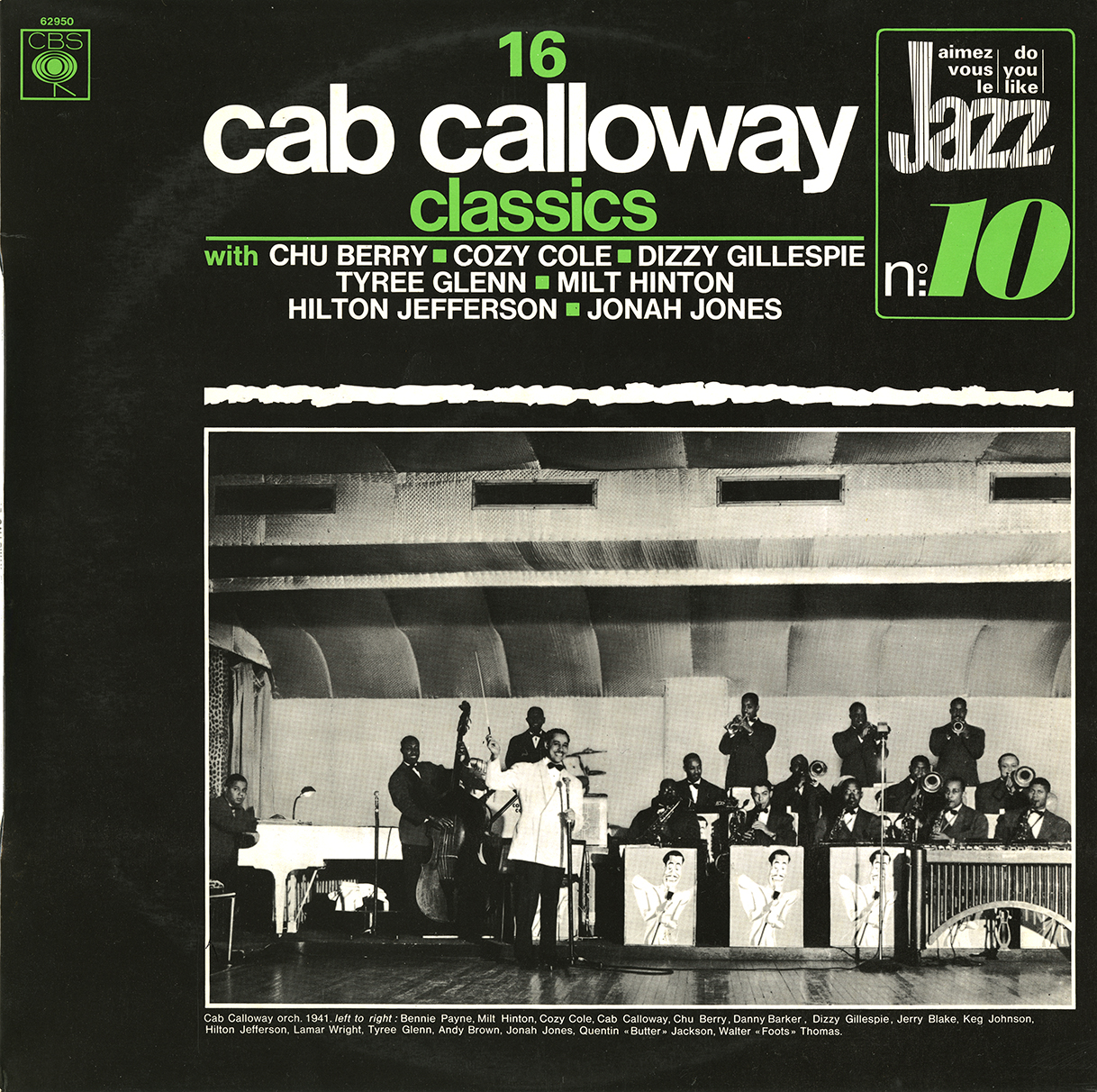

In 1936, Milt joined the Cab Calloway Orchestra, initially as a temporary replacement for Al Morgan while the band held a six-month residency at the newly opened midtown location of the Cotton Club in New York City. Milt quickly found acceptance among the band members, and he ended up staying with Calloway for over fifteen years. Until the Cotton Club closed in 1940, the Calloway band would perform there for up to six months per year, going on various tours for the remaining six months of the year. During the Cotton Club residencies, Hinton also took part in a number of recording sessions with Benny Goodman, Lionel Hampton, Billie Holiday, Ethel Waters, Teddy Wilson, and many others. It was at this time that Milt recorded what is possibly the first bass feature, “Pluckin’ the Bass” in August 1939.

Milt also first appeared regularly on radio while in Calloway’s band, either on bass in the context of concerts broadcast from the Cotton Club, or as a cast member for the short-lived music quiz show “Cab Calloway’s Quizzicale.” These broadcasts brought national attention to the Calloway band and helped enable the successful national tours the band would schedule. They also gave listeners a chance to hear examples of jive talk, which Calloway would formalize through publications such as his Hepster’s Dictionary, first published in 1938.

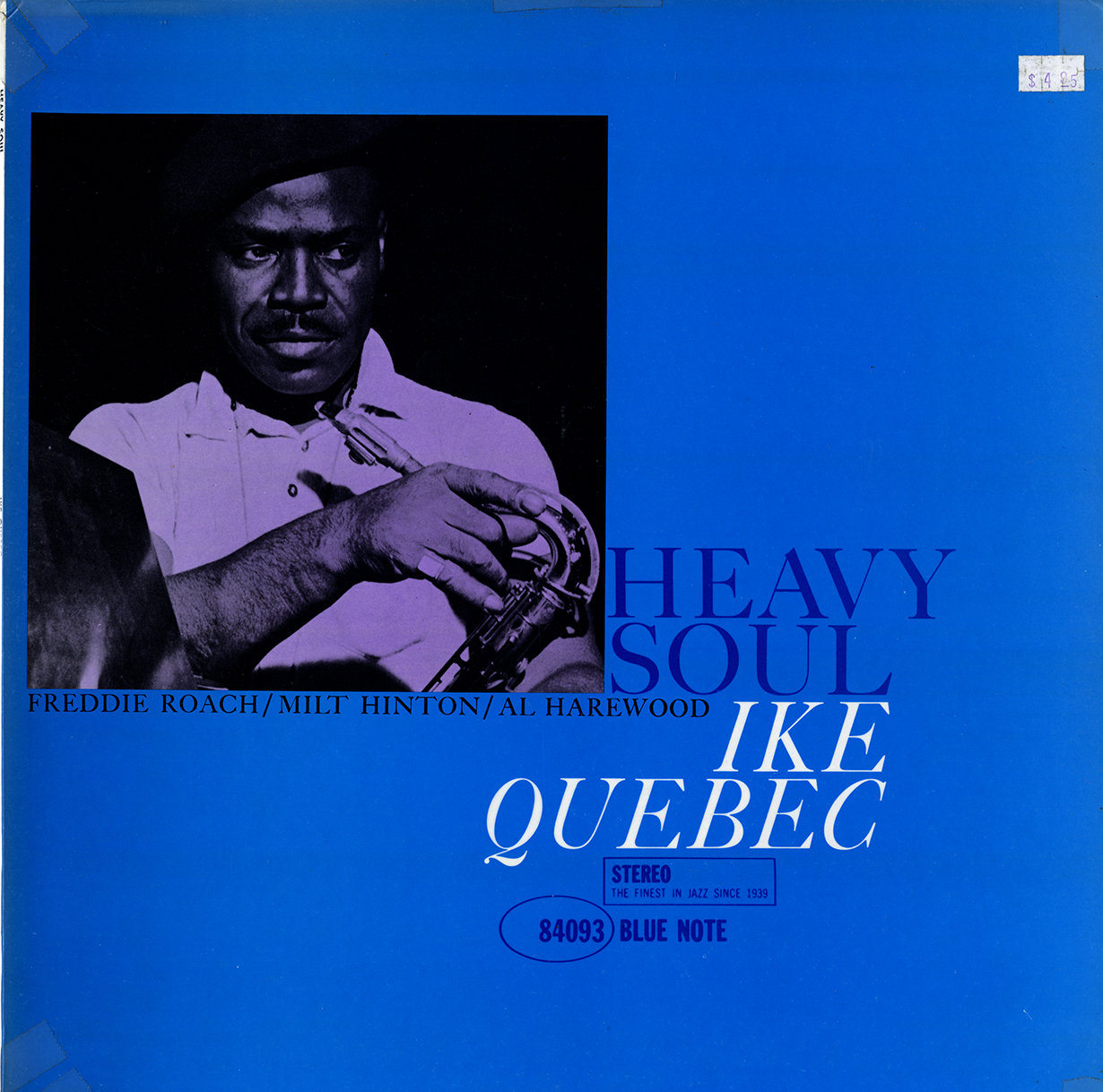

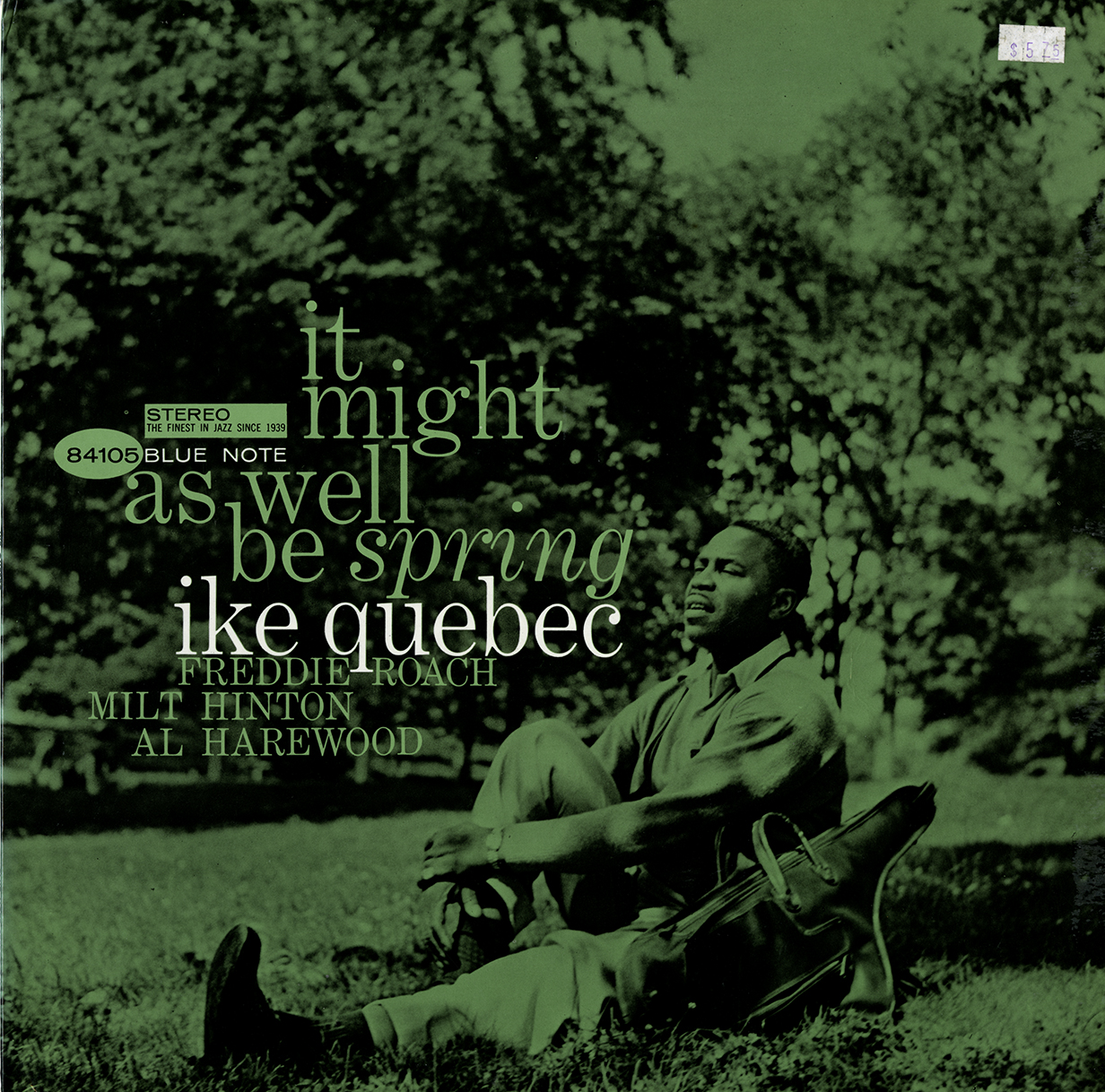

Calloway’s band included renowned sidemen such as Danny Barker, Chu Berry, Doc Cheatham, Cozy Cole, Dizzy Gillespie, Illinois Jacquet, Jonah Jones, Ike Quebec, and Ben Webster. Hinton credits Chu Berry with elevating the overall musicianship of the Calloway band in part by encouraging Cab to hire arrangers such as Benny Carter to create new arrangements that would challenge the musicians. As Hinton put it, “Musically he was the greatest thing that ever happened to the band.” Hinton was also heavily influenced by the musical innovations of Dizzy Gillespie, with whom he had informal sessions in the late 1930s during breaks between sets at the Cotton Club. Hinton credits Gillespie with introducing him to many of the experimental harmonic practices and chord substitutions that would later be associated with bebop.

In 1939 when Milt returned to Chicago for his grandmother’s funeral, he met Mona Clayton, who was then singing in his mother’s church choir. The two were married a few years later and remained inseparable for the rest of Milt’s life. (Mona was Milt’s second wife; the first was a brief relationship in the 1930s with Oby Allen, a friend Milt knew from high school.) Milt and Mona’s only child, Charlotte, was born on February 28, 1947. Mona had begun traveling with the Calloway Orchestra in the early 1940s - the only musician’s friend or spouse to do so. She helped musicians in the band manage their money, and she often insisted that they open savings accounts. For band members, she was a trusted confidant who was known for her discretion.

When traveling with a toddler became too difficult, the Hintons bought a two-family house in the Queens section of New York City, and ten years later they purchased a larger single-family home in an adjacent Queens neighborhood where they remained for the rest of their lives.

Mona played a critical role in Milt’s life and career. In addition to caring for their daughter, she handled all of the family’s finances, and her attention to detail ensured the couple’s financial security later in life. She kept track of Milt’s freelance work, scheduled interviews, coordinated public relations events, and often drove him back and forth to gigs (Milt never drove as an adult, due in part to a major car accident he was involved in as a teenager in Chicago). In the mid 1960s Mona completed both a bachelors and a masters degree and taught in the public schools for several years. In the 1970s, she began traveling with Milt again and was regularly invited to join him at the jazz parties and festivals where he performed. At the same time, she was active as a music contractor for Lena Horne and others. Mona was always well respected in the jazz community, and she and Milt were viewed by many as role models; as the jazz historian Dan Morgenstern noted in an article from 2000, “If there is a closer couple, I’d be surprised.”

Paystub from Cab Calloway to Milt Hinton (1947), The Milton J. and Mona C. Hinton Collection, Special Collections, Oberlin Conservatory Library.

After Cab (1950–1954)

By 1950, popular musical tastes had changed such that Calloway was no longer financially able to support a full big band. Instead, he hired Milt and a few others to create a smaller ensemble—first a septet and later a quartet—which toured with some regularity until June 1952, including trips to Cuba and Uruguay. After the Calloway ensemble disbanded, Milt began devoting more time to work as a freelance studio musician in New York City. At first, the work was sporadic, and, as Milt put it, “This was the one period in my life when I was worried about earning a living.” He supplemented by playing as many clubs and restaurants as possible, a practice he would continue for the next several decades. He performed regularly at La Vie en Rose, the Embers, the Metropole, and Basin Street West, where he appeared with Jackie Gleason, Phil Moore, and Joe Bushkin, among others. In the early 1950s he also performed for a brief time around the New York area with Count Basie.

Although his freelance work was steadily increasing, in July 1953 Hinton signed a one-year contract to go on tour with Louis Armstrong. He described the decision as “very difficult” as it would force him to be away from his family, and it would also slow down the momentum he was gaining as a freelance musician in New York City. The steady pay, along with the opportunity to perform with Armstrong won out, and Hinton performed dozens of concerts, including a tour of Japan, as a member of the band. When an opportunity to join the house band for a television show hosted by Robert Q. Lewis in New York opened up in February 1954, Hinton gave his notice to Armstrong and returned home to Queens.

In the studios (1954–1970)

For roughly the next two decades Hinton performed regularly on numerous radio and television programs, including those hosted by Jackie Gleason, Robert Q. Lewis, Galen Drake, Patti Page, Polly Bergen, Teddy Wilson, Mitch Miller, Dick Cavett, and others. As he recalled,

I had a great situation because I was never on staff. That meant I’d get paid by the show. And since I never spent more than fifteen hours a week on rehearsals and shows, I always had free time to do record dates.

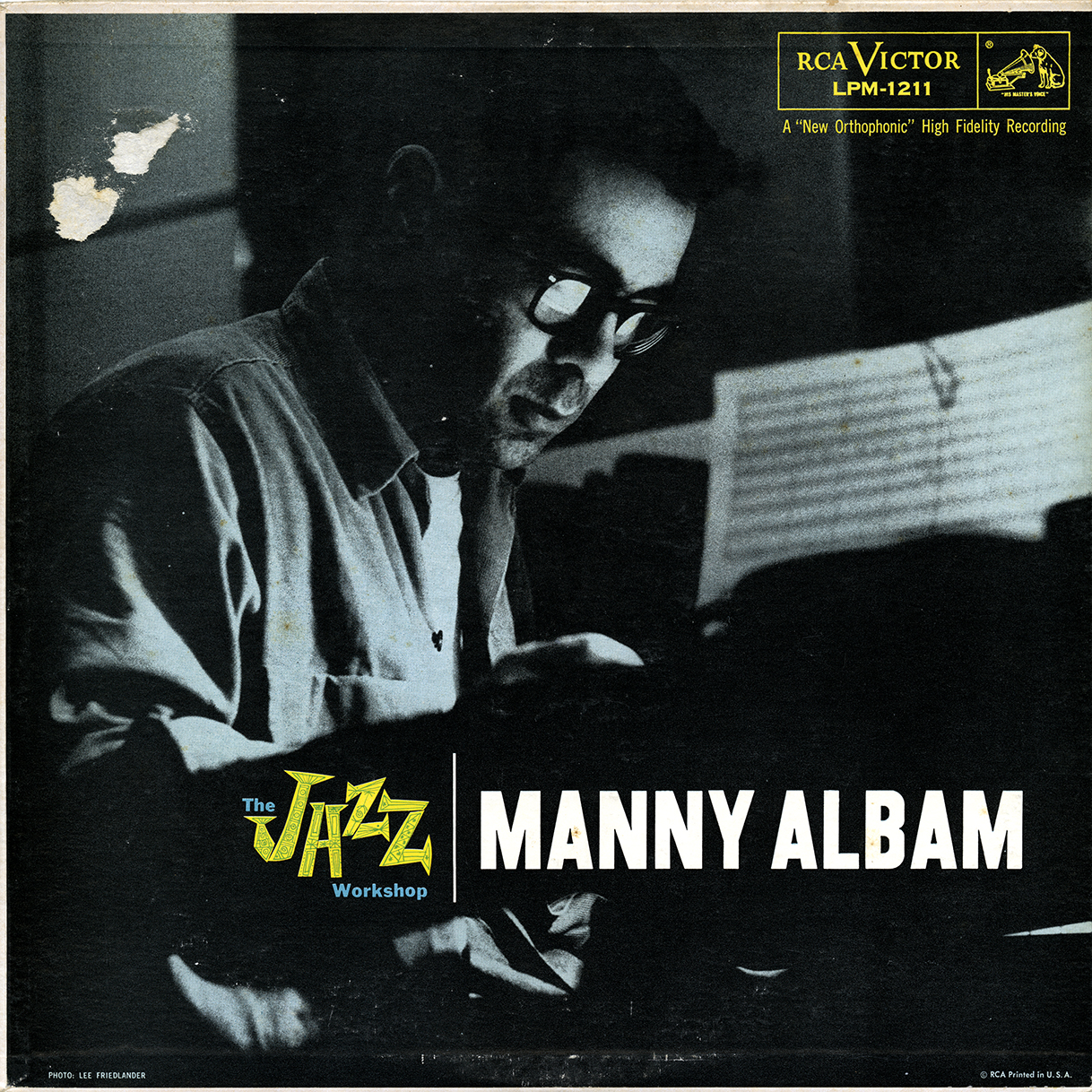

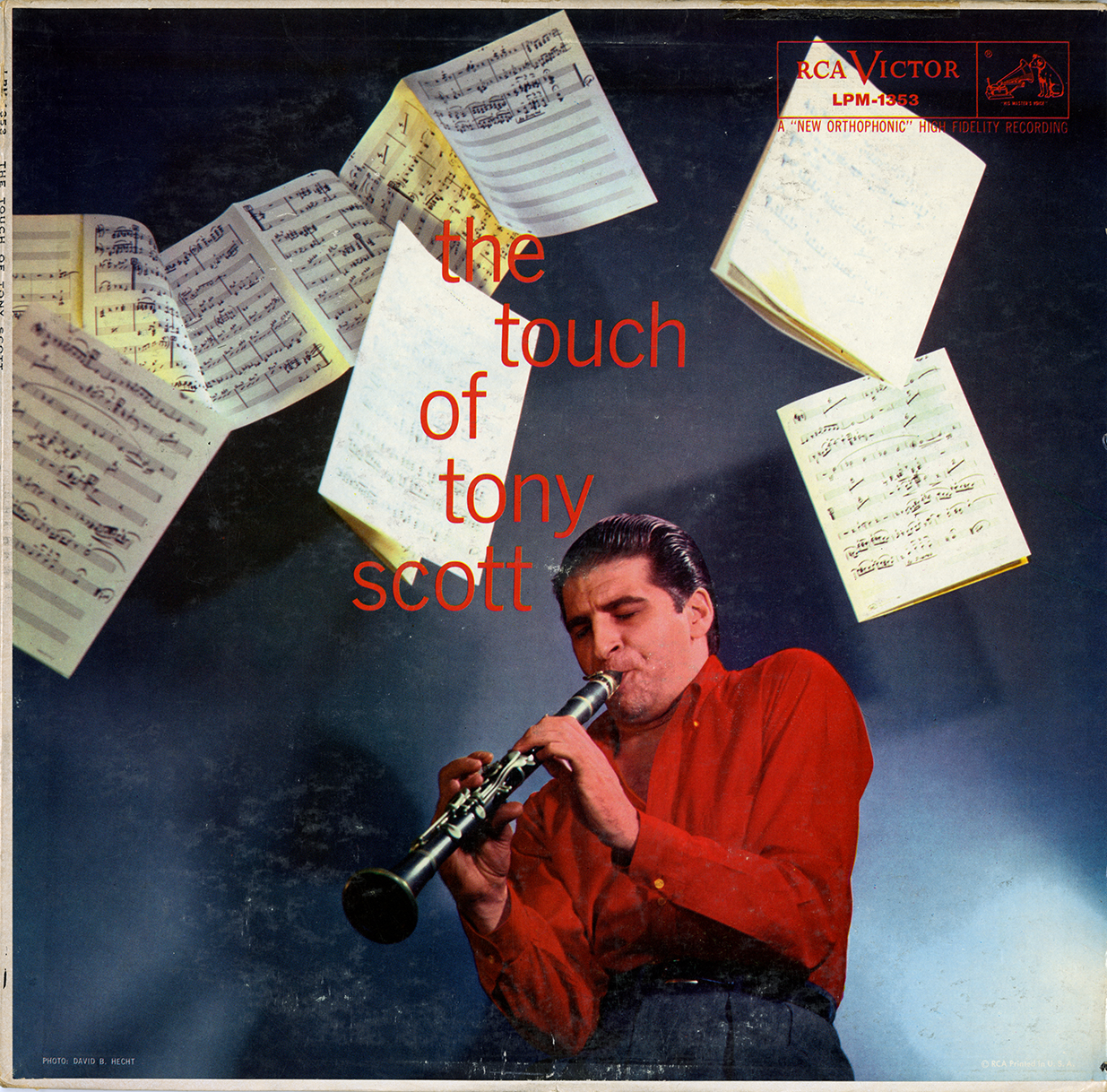

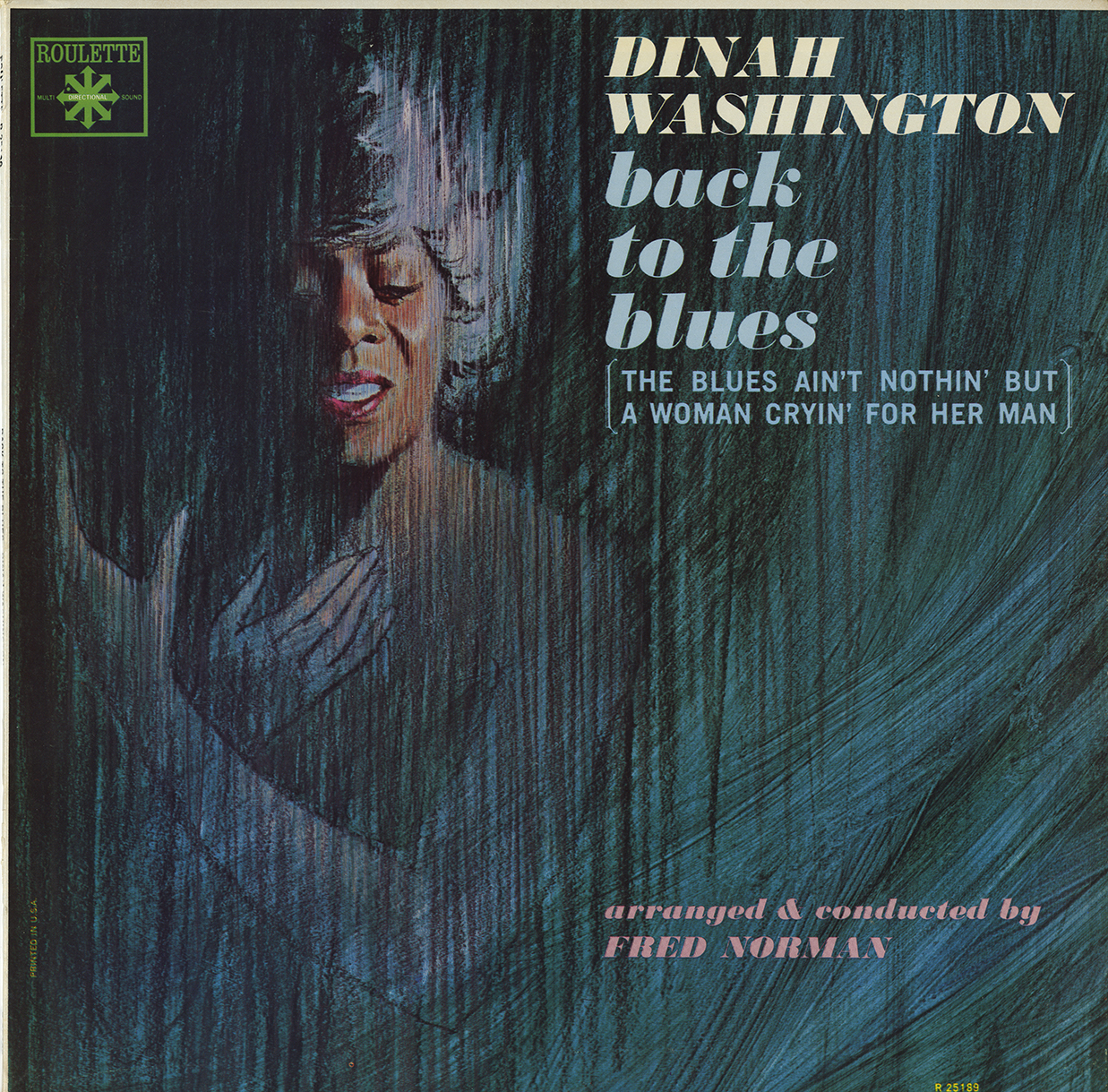

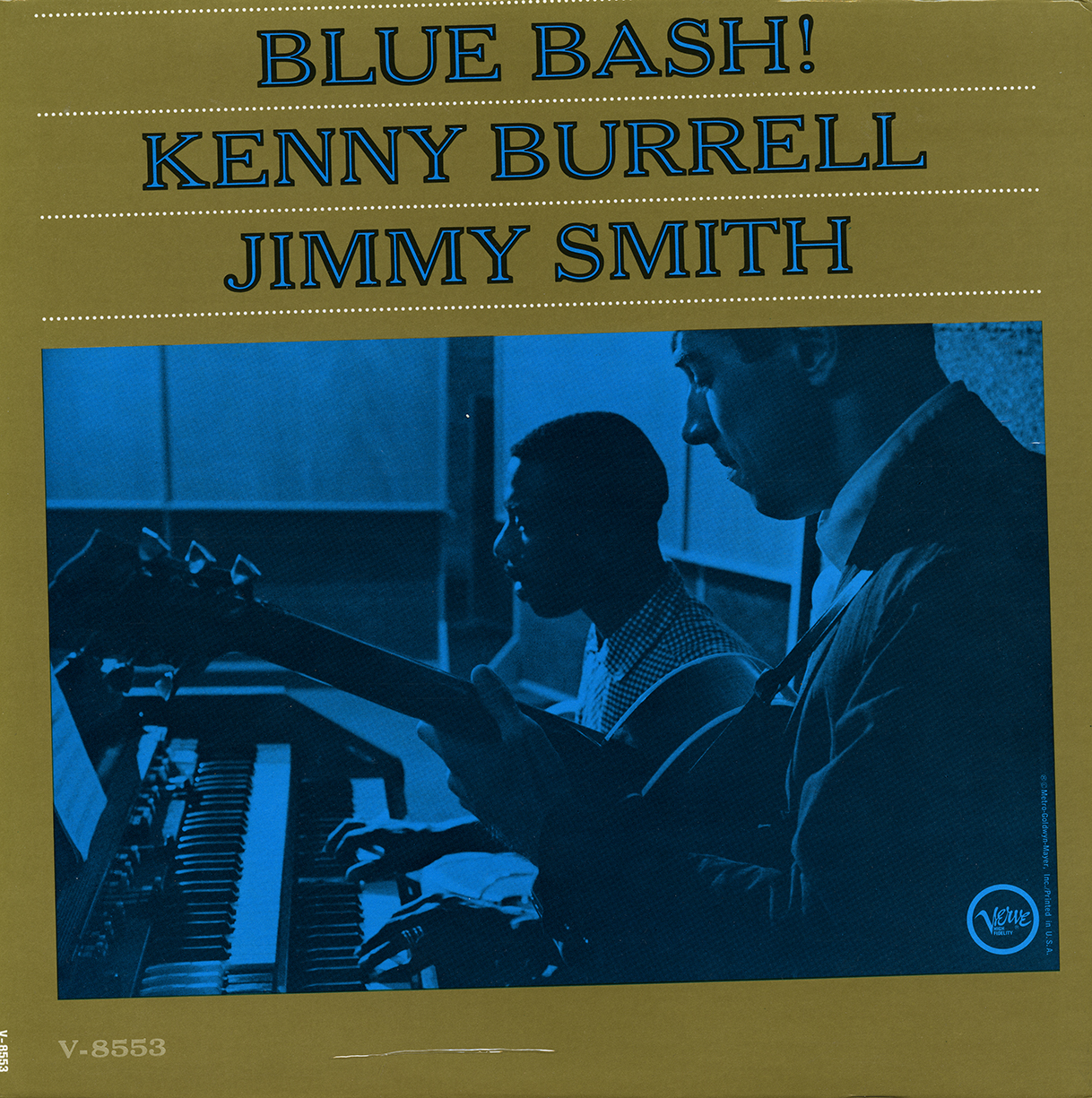

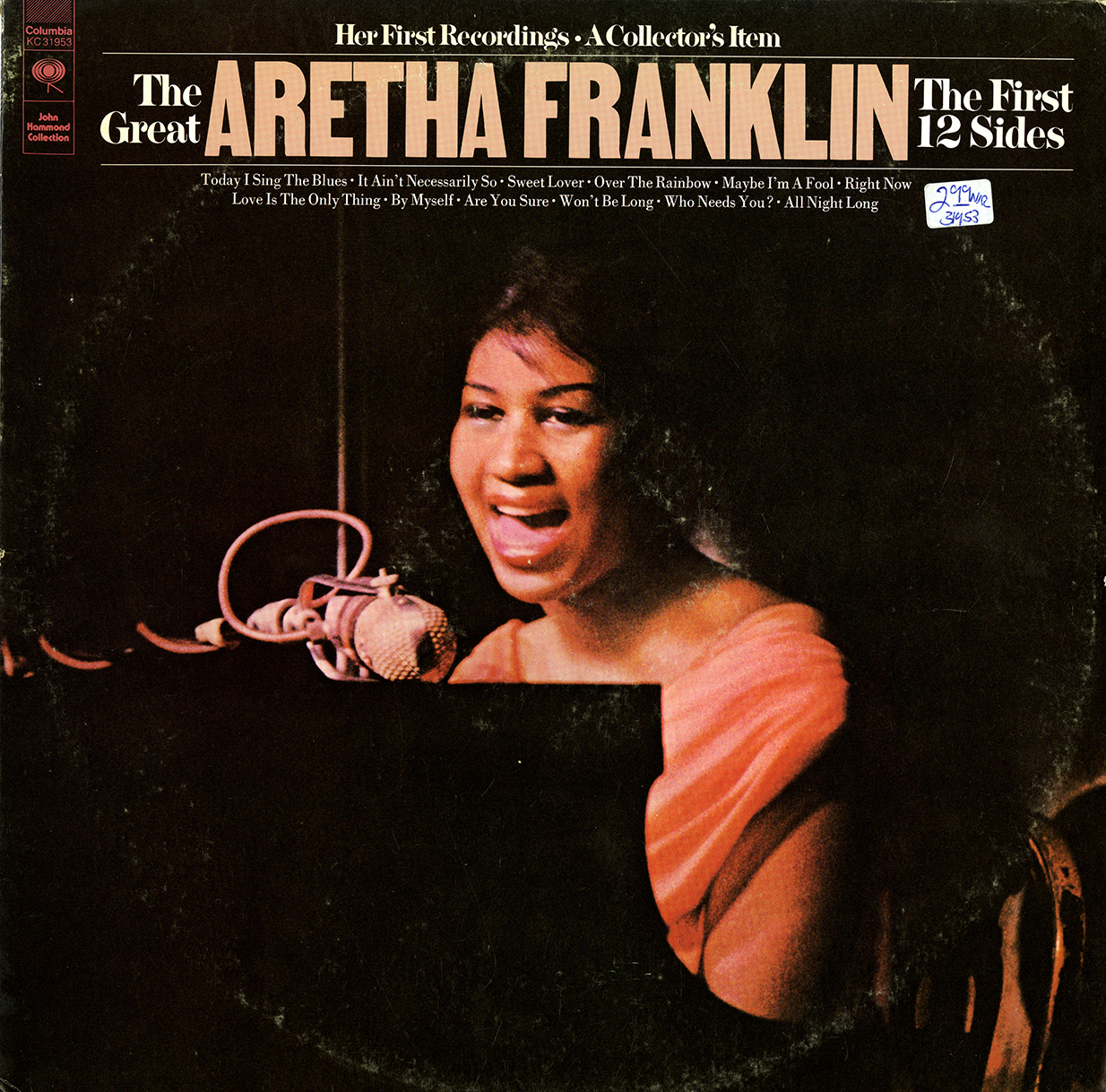

By far, Hinton’s most regular work during this era was in the recording studio, where he was among the first African-Americans to be regularly hired for studio contract work. From the mid-1950s through the early 1970s he contributed to thousands of jazz and popular records as well as hundreds of jingles and film soundtracks. He would regularly play on three three-hour studio sessions per day, requiring him to own multiple basses that he hired assistants to transport from one studio to the next. During this era Milt recorded with everyone from Billie Holiday to Paul McCartney, Frank Sinatra to Leon Redbone, and Sam Cooke to Barbra Streisand. As Hinton summarized his time in the studios,

I might be on a date for Andre Kostelanetz in the morning, do one with Brook Benton or Johnny Mathis in the afternoon, and then finish up the day with Paul Anka or Bobby Rydell. At one time or another, I probably played for just about every popular artist around in those days.

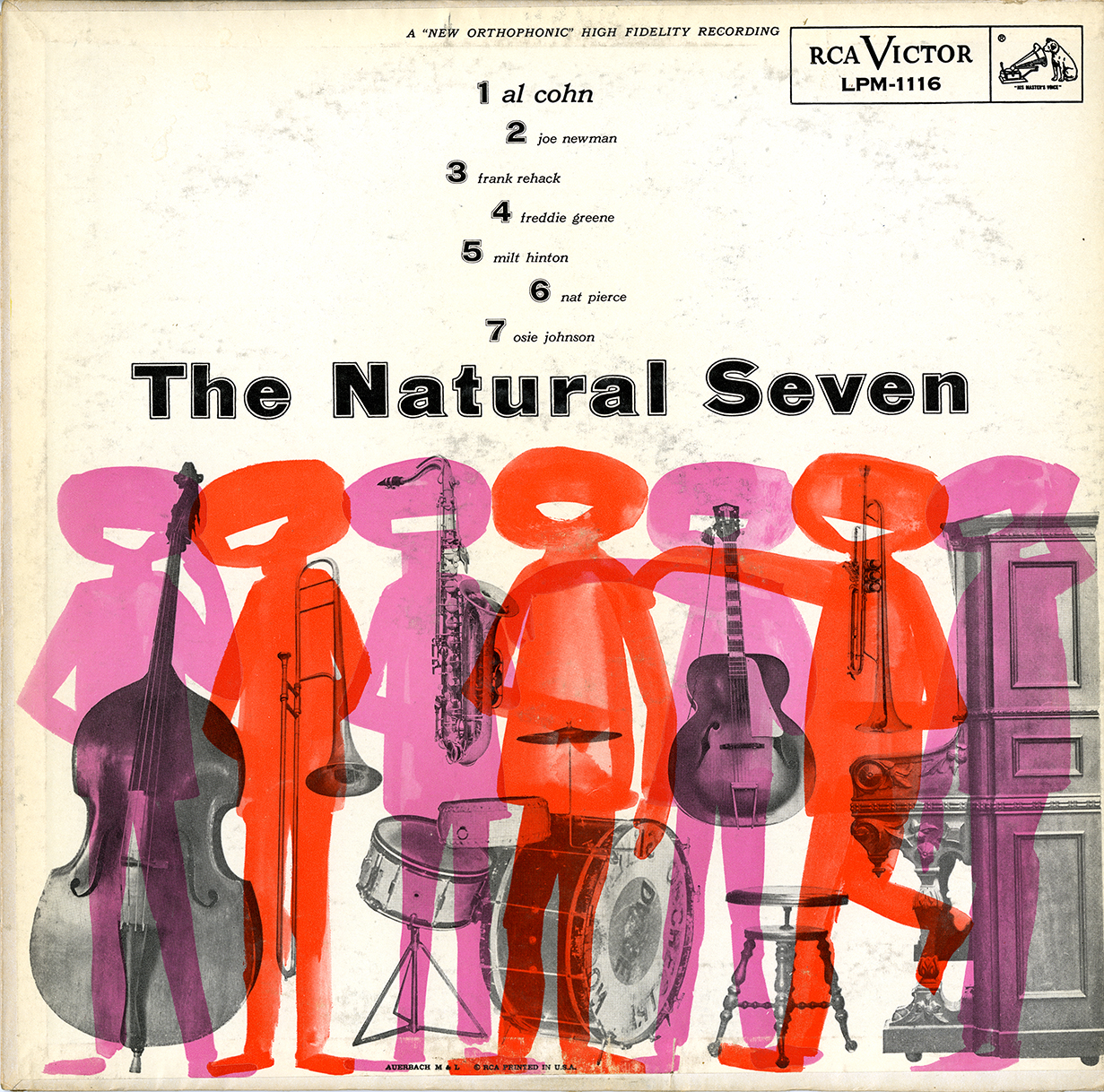

Starting in the middle 1950s, Hinton regularly worked in the studio with Hank Jones (piano), Barry Galbraith (guitar), and Osie Johnson (drums) in a group that informally became known as the New York Rhythm Section. The four played on hundreds of sessions together and even recorded an LP in 1956 entitled The Rhythm Section.

Milt Hinton’s personal datebook (1959), The Milton J. and Mona C. Hinton Collection, Special Collections, Oberlin Conservatory Library.

After the studios (1970–2000)

By the late 1960s studio work began dropping off, so Hinton incorporated more live performances into his schedule. He regularly accepted club gigs, most often at Michael’s Pub, Zinno’s, and the Rainbow Room where he performed with Benny Goodman, Johnny Hartman, Dick Hyman, Red Norvo, Teddy Wilson, and others. He also went back on the road, first with Diahann Carroll for a tour in Paris in 1966, and later with Paul Anka, Barbra Streisand, Pearl Bailey, and Bing Crosby. From the 1960s through the 1990s he traveled extensively to Europe, Canada, South America, Japan, the Soviet Union, and the Middle East, while also appearing throughout the U.S.

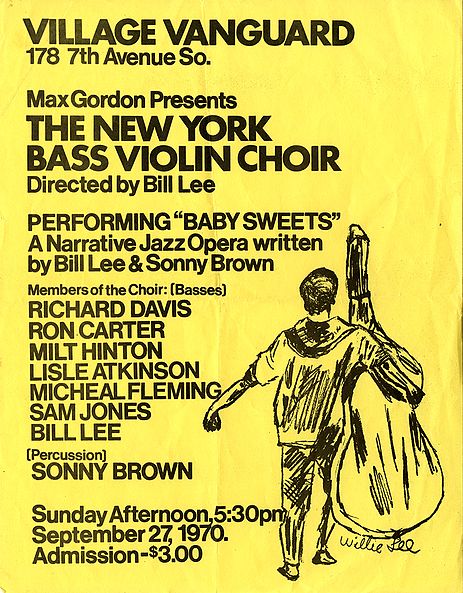

In 1968 Hinton began performing as a part of Professionals Unlimited (later renamed the New York Bass Violin Choir), a collective bass ensemble organized by Bill Lee that included Lisle Atkinson, Ron Carter, Richard Davis, Michael Fleming, Percy Heath, and Sam Jones. The group performed irregularly for a number of years and in 1980 released a self-titled album on the Strata-East label (SES-8003) containing material recorded between 1969-1975.

Milt also taught for nearly twenty years as a visiting professor of jazz studies at Hunter College and Baruch College, first offering a jazz workshop at Hunter in the fall of 1973. During this time he regularly appeared at jazz festivals, parties, and cruises; performing annually at Dick Gibson’s jazz parties in Colorado, the Odessa and Midland jazz parties in Texas beginning in 1967, and Don and Sue Miller’s jazz parties in Phoenix and Scottsdale.

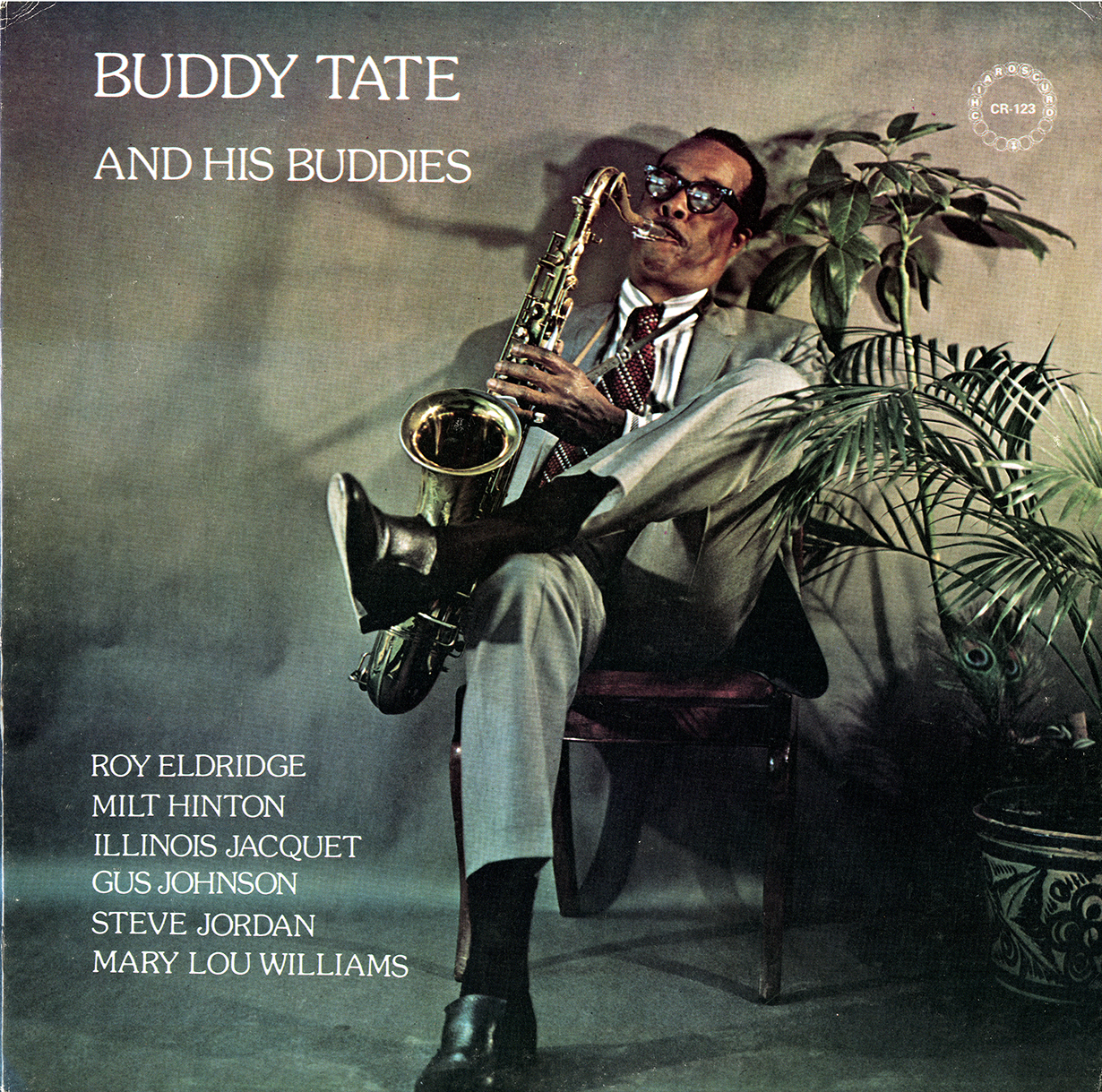

Milt played at the first Newport Jazz Festival in 1954 and was a regular at Newport and other jazz festivals produced by George Wein throughout the next four decades. He was a favorite at the Bern Jazz Festival in Switzerland, sponsored by Hans Zurbruegg and Marianne Gauer. For much of the 1980s and 1990s Hinton was featured on jazz cruises organized by Hank O’Neal, then owner of Chiaroscuro Records.

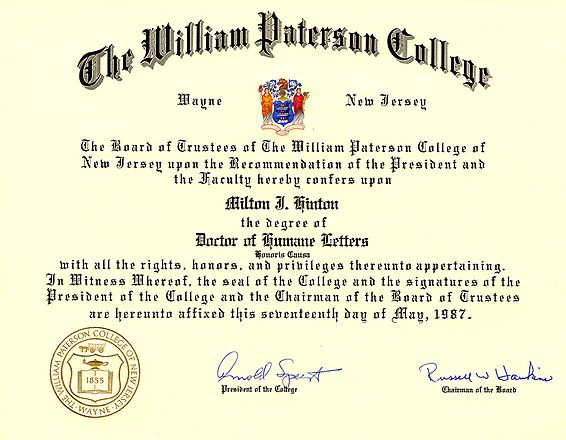

By the 1990s Milt was revered as an elder statesman in jazz, and he was regularly honored with significant awards and accolades. He received honorary doctorates from William Paterson College, Skidmore College, Hamilton College, DePaul University, Trinity College, the Berklee College of Music, Fairfield University, and Baruch College of the City University of New York. He won the Eubie Award from the New York Chapter of the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, the Living Treasure Award from the Smithsonian Institution, and he was the first recipient of the Three Keys Award in Bern, Switzerland. In 1993, Milt was awarded the highly prestigious National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master Fellowship. He also contributed to the NEA’s Jazz Oral History Program, continuing a longstanding practice of recording interviews with friends in his basement during extended visits. In 1996 he received a New York State Governor’s Arts Award, in March 1998 he was awarded the Artist Achievement Award by the Governor of Mississippi, and in 2000 his name was installed on ASCAP’s Wall of Fame.

In 1990, Milt’s 80th year, WRTI-FM in Philadelphia produced a series of twenty-eight short programs in which Milt chronicled his life. These were aired nationwide by more than one hundred fifty public radio stations and received a Gabriel Award that year as Best National Short Feature. In the same year George Wein produced a concert as a part of the JVC Jazz Festival in honor of Milt’s 80th birthday. Similar concerts were produced for his 85th and 90th birthdays. By 1996, Milt ceased performing on bass, due to a number of physical ailments, and he passed away at the age of 90 on December 19, 2000.

Flyer for 1970 performance of the New York Bass Violin Choir, The Milton J. and Mona C. Hinton Collection, Special Collections, Oberlin Conservatory Library.

Honorary doctorate diploma awarded to Milt Hinton by William Patterson College (1987), The Milton J. and Mona C. Hinton Collection, Special Collections, Oberlin Conservatory Library.

Musicianship

Milt was broadly regarded as a consummate sideman, possessing a sensitivity for appropriately applying his formidable technique along with his extensive harmonic knowledge to the performance at hand. He was equally adept at bowing, pizzicato, and “slapping,” a technique for which he first became famous while playing with the Cab Calloway Orchestra early in his career. He was also an accomplished sight-reader, a skill which he developed on the road with Calloway and honed during his several decades of studio work. As he described his technical diversity,

Working with Cab for sixteen years could have made me stale. You play the same music over and over, and after awhile you can do it in your sleep. Many guys liked it that way because it was easy. But when the band business got bad, they weren’t prepared to do anything else. On the other hand, I was able to work on radio and TV and get all kinds of record dates. In a real way, practicing and discipline paid off.

In the archives...

Learn more about the Milton J. and Mona C. Hinton collection at the Oberlin Conservatory Library!